In most cultures, vengeful spirits are feared, exorcised, or forgotten.

But in Japan, even the wrathful dead are embraced.

Through the act of matsuru—ritual remembrance and reconciliation—Japan transforms resentment into harmony, and injustice into moral reflection.

This is not superstition. This is a living philosophy of dignity, deeply woven into the spirit of bushidō.

Introduction

In Japanese culture, there exists a spiritual worldview distinct from those of other civilizations—a worldview in which even the dead who died in resentment are not rejected but instead are honored through ritual. One of the most remarkable expressions of this worldview is the tradition known as onryō shinkō, or “belief in vengeful spirits.” In most cultures, vengeful spirits are feared, exorcised, or dismissed. In Japan, they are often matsuru—a term that encompasses appeasing, honoring, and ritually enshrining. These spirits are not banished but welcomed into the moral order.

This essay explores the cultural and ethical underpinnings of onryō shinkō, and how this belief system reflects a deeper Japanese philosophy of justice, reconciliation, and communal harmony.

1. The Origins of Onryō Belief

One of the earliest and most prominent examples of onryō shinkō—the belief in vengeful spirits—can be found in the deification of Sugawara no Michizane in the early 10th century. A scholar and statesman of great integrity, Michizane opposed the powerful Fujiwara clan’s monopolization of political power and foreign trade, particularly the Tang Dynasty missions. Viewing these missions as detrimental to the people despite their economic benefit to the elites, he proposed their abolition for the sake of national well-being.

Though his intentions were rooted in loyalty and moral responsibility, his stance threatened vested interests. As a result, Michizane was falsely accused and exiled to Dazaifu, where he died in sorrow and disgrace. After his death, Kyoto was struck by a series of natural disasters, plagues, and fires—events that were widely interpreted as the wrath of his restless spirit.

In response, the imperial court built the Kitano Tenmangū Shrine to appease his soul. Over time, Michizane was deified as Tenjin, the god of learning. His transformation from a wronged man to a revered deity illustrates how Japanese culture ritualizes unresolved injustice—not through denial or erasure, but through reverent inclusion—transforming grief and anger into sacred memory and a cultural act of restoring social harmony.

2. The Cultural Significance of Matsuru

Matsuru is an untranslatable concept in its full depth. It implies not just ritual but also emotional and spiritual acceptance. In the Japanese worldview, what is feared is not necessarily rejected. Earthquakes, typhoons, even plagues are not only destructive—they are divine. In Shinto, they are called aragami—wrathful deities whose power must be appeased and integrated.

Matsuru thus becomes a central ethic: do not eliminate the threatening force—commune with it. Onryō shinkō is a spiritual practice of welcoming even the angry or wronged dead into the moral community. Their grievances become an opportunity for the living to restore ethical balance. Their spirits are not reminders of fear, but of accountability.

3. The Essence of Onryō: Unacknowledged Justice

Onryō are not simply ghosts of anger. They are manifestations of justice that society failed to uphold. Sugawara no Michizane’s story is not one of personal vengeance—it is a historical indictment of political greed and systemic injustice. That his posthumous transformation into a deity resonated so widely shows that the public, too, recognized and internalized that moral failure.

To appease an onryō is to admit wrong, to repent, and to realign one’s society with the values it had forgotten. This makes matsuru a profoundly ethical act: it ritualizes the process of truth-telling and reconciliation.

4. Contemporary Relevance of Onryō Shinkō

In the modern world, injustice still breeds resentment. Political corruption, social inequality, disinformation, and public betrayals are today’s catalysts for spiritual unrest—not of ghosts, but of collective anger. If not addressed, these forces fracture societies.

What onryō shinkō teaches us is that the way forward is not through suppression, nor revenge, but through remembrance, humility, and ethical repair. In this way, matsuru becomes a model for social healing: acknowledging pain not to dwell in it, but to elevate it.

5. The Way of the Warrior

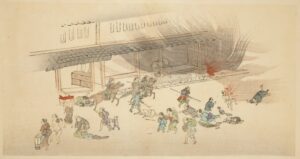

Two centuries after Michizane’s death, the warrior class would rise to power in Japan. The samurai, inheriting this tradition, too, developed a practice of matsuru. After battles, they would honor not only their own dead but also the defeated—burying them with dignity, offering prayers, and preserving their names. They understood that true victory lay not in domination, but in restoring harmony after conflict.

This ethic forms a bridge between onryō shinkō and bushidō, the way of the warrior. It reminds us that even in violence, there must be justice; even in death, there must be dignity.

Conclusion

Onryō shinkō is not a relic of folklore. It is a living moral framework, deeply embedded in Japan’s cultural DNA. It teaches that when society forgets justice, the spirits remind us—and when we remember, we do not destroy what is feared, but we matsuru it.

To matsuru is to reconcile, to reweave the social fabric, and to walk again toward the way of peace. In this sense, onryō shinkō and bushidō are not separate paths—they are two expressions of the same soul.