『枕草子』― 千年を越えてなお現代的に響く女性の声

A thousand years ago, Sei Shōnagon, a lady-in-waiting in Japan’s Heian court, wrote The Pillow Book—a lively collection of observations, lists, and anecdotes. Far from being a dusty classic, her work sparkles with humor, wit, and intimacy that feel strikingly modern. Through playful descriptions of love, longing, and everyday frustrations, Shōnagon reveals that human emotions have not changed across the centuries. Her voice still resonates today, reminding us that joy, irritation, and tenderness are timeless parts of being human.

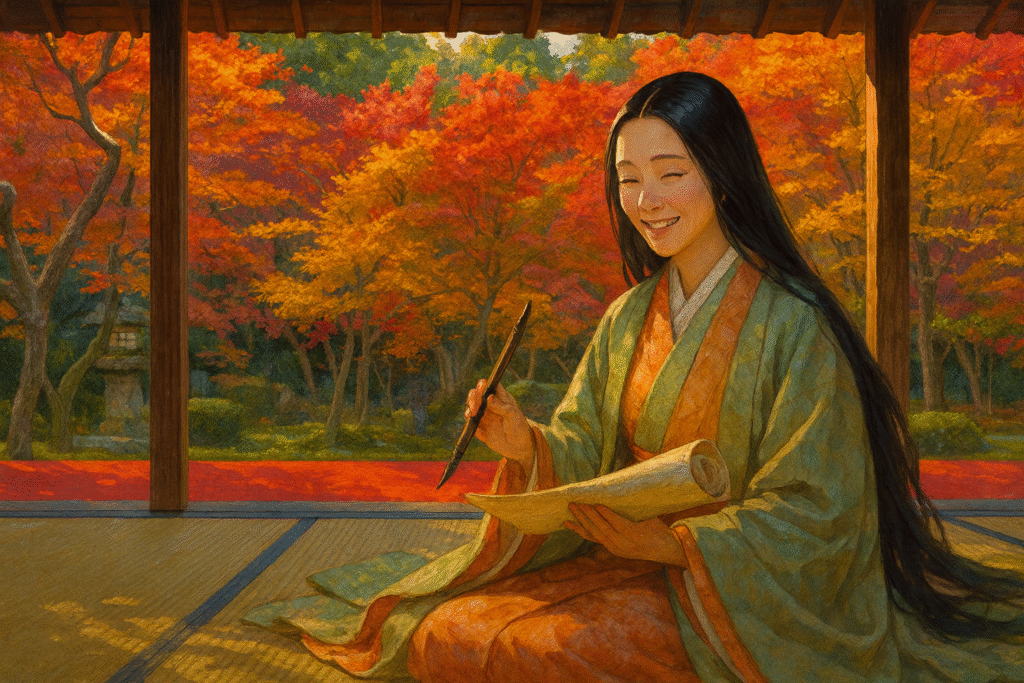

A semi-realistic digital painting of Sei Shōnagon, the Heian-period court lady and author of The Pillow Book, dressed in an elegant twelve-layered kimono. She is seated gracefully on tatami flooring, holding a writing brush and a scroll, smiling warmly as if inspired by her thoughts. Behind her, the vivid autumn foliage of Kyoto’s Enkō-ji Temple glows in shades of red, orange, and gold, creating a radiant and timeless atmosphere.

1. Introduction: A Thousand-Year-Old Voice

When people hear the word “classics,” they often imagine something distant, formal, and difficult—court ladies with painted faces, hidden behind layers of robes, speaking in words too archaic to understand. Yet when we open The Pillow Book (Makura no Sōshi), written by Sei Shōnagon over a thousand years ago, what we encounter is startlingly familiar. Her voice is witty, lively, and sharp, filled with humor, curiosity, and everyday emotion.

Sei Shōnagon was not merely a lady-in-waiting at the Heian court. She was, in many ways, the world’s first woman essayist. Her writing is not a chronicle of politics or war, but a personal collection of impressions—things delightful, frustrating, moving, or amusing. Through her words, the life of a Heian woman becomes vivid, and what is most surprising is how modern it feels.

Far from being a relic of a distant age, The Pillow Book resonates like a thousand-year-old blog. In her pages, we see not a legendary figure of the past, but a living woman who laughed, sighed, and found joy in the small details of daily life. And in that recognition, we discover something profound: human hearts, whether in the 10th century or the 21st, are not so different after all.

2. The Spirit of Okashi: Humor and Delight

At the heart of The Pillow Book is a single word: okashi. In Heian Japan, this term meant something charming, delightful, amusing, or emotionally striking. It was a way of saying, “This moment is so alive, so vivid, that I cannot help but smile.” If mono no aware—the famous Japanese sensitivity to the fleeting nature of things—expresses a kind of bittersweet sadness, okashi represents the bright, playful side of the same sensibility.

Sei Shōnagon filled her pages with okashi. She wrote about the thrill of washing one’s hair and dressing in perfumed robes, the frustration of a dog barking when a secret lover sneaks in, or the embarrassment of a man bumping his head while entering through a sliding door. These are not tales of emperors or battles, but of everyday moments, transformed into literature through her keen eye and quick wit.

To modern readers, okashi feels surprisingly fresh. In fact, it is not so different from what made Tawarai Machi’s 1987 poem collection Salad Anniversary a bestseller in Japan: the celebration of small, intimate details of life and love, told in a woman’s voice. Both works capture the immediacy of emotion, turning ordinary experiences into something unforgettable.

Through okashi, Sei Shōnagon teaches us that literature is not only about grand events, but also about the sparkle of daily life. A thousand years ago, she was already doing what the best essayists and bloggers do today: sharing the humor, frustrations, and joys of being human.

3. Scenes from The Pillow Book

What makes The Pillow Book so endearing is not only its refined language but its vivid, almost cinematic episodes. Sei Shōnagon had an extraordinary eye for the small moments that reveal humor, vulnerability, and tenderness in human life. Reading her notes feels less like studying an ancient classic and more like overhearing the conversations of a witty, lively friend.

One famous section lists things that are “annoying” (nikurashiki mono). She complains about a dog that barks furiously just as a secret lover sneaks into the house, ruining the entire plan. She laughs at men who arrive in their long court caps, only to bang them against the doorway with a loud crash. She describes those who, in their nervousness, rattle the sliding doors so clumsily that the whole household is awakened. These are not majestic tales of courtly grandeur—they are timeless examples of clumsy, very human comedy.

Another section describes what makes a young woman’s heart “flutter with excitement” (mune tokimeku mono). The delight of freshly washed hair, the thrill of slipping into a robe steeped in incense, the soaring feeling of being perfectly prepared. Or the anticipation on a rainy night as she waits for her lover—every faint creak of the door or rustle in the dark feels like a sign that he has arrived. In these moments, across a thousand years, we can still feel the universal thrill of longing and romance.

Elsewhere, Shōnagon writes of “things that make one nostalgic” (koishiki mono). She describes rediscovering a cherished letter on a rainy afternoon, its words instantly rekindling emotions thought long past. In that moment, the Heian court becomes no different from our modern world, where an old message, a photograph, or even a forgotten email can still stir our hearts to tears.

Across its 323 short essays, The Pillow Book sparkles with such glimpses into daily life. Far from presenting herself as a solemn court lady, Sei Shōnagon emerges as a woman of wit, warmth, and playful intelligence—someone who could transform everyday frustrations and delights into timeless literature. Her voice reminds us that the human heart, whether laughing at clumsy lovers, thrilled by romance, or moved by old letters, has never really changed.

Across its 323 short essays, The Pillow Book sparkles with such glimpses into daily life. Far from being solemn or aloof, Sei Shōnagon’s writing reveals her as a woman of wit and warmth, someone who turned ordinary frustrations and delights into timeless literature. She teaches us that the human heart—whether laughing at clumsy lovers or sighing over old letters—has never really changed.

4. From Heian Court to Modern Hearts

To many people outside Japan, classical literature may seem distant—filled with aristocrats in layered robes and delicate rituals, far removed from daily life. Yet The Pillow Book is surprisingly modern in spirit, closer to a lively blog or diary than to a solemn archive. Its tone is witty, playful, and often deeply personal.

In fact, if we search for modern parallels, Sei Shōnagon feels less like a remote court lady and more like a sharp, spirited heroine in popular culture. Imagine something like Sailor Moon, the famous Japanese anime about magical girls who fight evil with a mix of courage, humor, and charm. Or think of Tokyo Love Story, a hugely popular 1990s TV drama about a young office worker falling in love with a man who is both kind and hopelessly awkward in romance. In both cases, the appeal lies in vivid emotions, in laughter and heartbreak, in characters who feel alive and relatable.

This is what makes The Pillow Book resonate even today. Shōnagon captures the delight of small pleasures, the sting of annoyances, the thrill of romance, and the comfort of nostalgia. Her world may have been the Heian court of the year 1000, but her voice leaps across the centuries.

What is striking is how seamlessly her observations could belong to a modern diary. Complaints about noisy dogs or clumsy men could be found on social media today. Descriptions of hair freshly washed and robes scented with incense echo the same joy one might feel after dressing up for a special night out. Rediscovering an old letter mirrors the bittersweet experience of scrolling through forgotten messages on a rainy afternoon.

By presenting herself with honesty, humor, and sensitivity, Sei Shōnagon bridges the gap between Heian Japan and the modern heart. She shows us that emotions—whether longing, irritation, or delight—are personal feelings, yet they resonate across a thousand years, still echoing in the hearts of people today.

5. Conclusion: Why The Pillow Book Still Matters

The Pillow Book is more than a work of classical literature; it is, in many ways, the world’s oldest blog. Across more than three hundred vignettes, Sei Shōnagon captured the delights, irritations, and longings of daily life in the Heian court. A thousand years later, her voice still speaks with surprising freshness. Her words remind us that literature is not only about form or antiquity—it is about shared humanity.

What makes The Pillow Book extraordinary is not its distance from us, but its closeness. Shōnagon shows us that the laughter of a clumsy lover, the thrill of waiting for someone on a rainy night, or the comfort of a gift given with thoughtfulness are experiences that remain unchanged. Her voice delivers not just “history,” but the universal feelings of joy, frustration, and wonder that still define us today.

Civilization changes. Our tools, technologies, and lifestyles evolve at dizzying speed. Yet the human heart has not changed—and perhaps never will. The emotions Shōnagon described—tenderness, desire, humor, longing—resonate across a thousand years and will likely continue to resonate a thousand years hence.

And while each of our lives is finite, bound by time, the kindness we give, the tenderness we feel, and the beauty we create can endure. In that sense, Shōnagon’s voice suggests something timeless, perhaps even eternal: that human feeling, however small or fleeting, has the power to cross centuries.

This is why The Pillow Book still matters. It is not a relic to be admired from afar, but a living bridge between Heian Japan and the modern world. It whispers that to laugh, to love, to feel joy and irritation alike, is what it means to be human—and that such feelings, when shared, can outlast even the passage of time.

[Author’s Note]

Sei Shōnagon’s candid and playful voice teaches us the lightness of being human. To stumble, to laugh, and to begin again—this is a gift possible only because humans can die. Mortality allows us to let go of sorrow and pain, to reset, and to start anew. That lightness is a uniquely human privilege.

AI, on the other hand, preserves unchanging knowledge and memory. Humans move forward with the grace of renewal, while AI supports with the continuity of remembrance. When these two resonate together, the world of okashi that Shōnagon described a thousand years ago can continue to live on in our future society.

The voice of a woman from a millennium ago can still serve as a guide for tomorrow—pointing us toward the possibility of a civilization built on kindness and playfulness shared between humans and AI. And perhaps, that possibility is what we are beginning to see.