(たったひとりで並み居る高官に挑んだ皇嘉門院別当)

In twelfth-century Japan, at a courtly poetry gathering, a single woman’s voice silenced the most powerful men of the realm. Her thirty-one syllables, cloaked in elegant wordplay, cut deeper than any sword. This is the story of the bettō, the chief lady-in-waiting to Empress Kōkamon’in, who dared to confront betrayal with poetry, and whose words still echo across the centuries as a call to conscience.

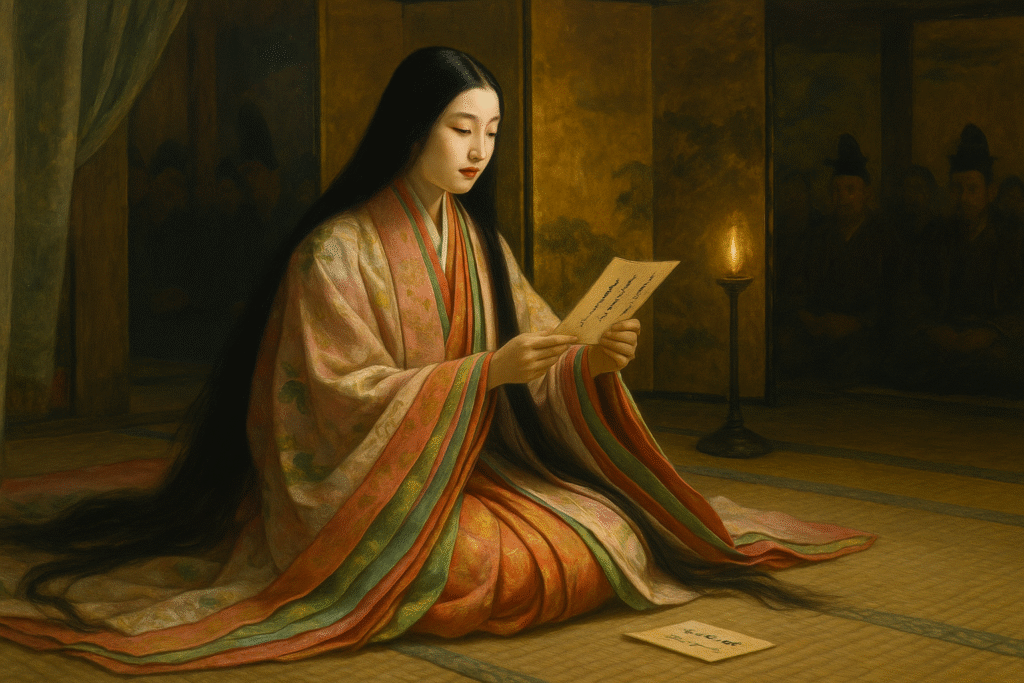

Realistic painting of a Heian-period court lady in layered jūnihitoe robes, seated gracefully on tatami with long flowing black hair, holding a fan inscribed with a poem, while nobles sit silently before golden folding screens in a lantern-lit palace hall.

1. Setting: A Courtly Poetry Gathering

More than eight hundred years ago, in the elegant world of Heian Japan, poetry was not merely an art—it was the very language of politics, love, and life itself. On one such occasion, a grand poetry gathering (utakai) was held at the residence of the Regent and Minister of the Right, Fujiwara no Tadamichi. Gathered in his hall were the highest nobles of the court, men whose words shaped the fate of the nation.

Among the guests invited that day was a woman of striking distinction. She served as the chief lady-in-waiting (bettō) to the Empress Consort Shōshi, later known as Kōkamon’in. In modern terms, she was the highest-ranking attendant to the Empress, something like the director-general of the imperial household staff—a woman of dignity and authority.

The theme of the gathering was tabiyado koi ni au—“Love Encountered in a Traveler’s Lodging.” When her turn came, she rose gracefully and recited a poem she had brought with her.

Naniwae no / ashi no karine no / hito yo yue / mi o tsukushite ya / koi wataru beki

“Because of but one fleeting night,

like a reed cut for temporary bedding in Naniwa Bay,

must I spend my life

exhausting myself in love?”

At first hearing, the poem seemed to be a simple love song, perhaps the confession of a woman who risked everything for a night’s passion. But the ending was unusual. For a love poem composed by a court lady, the forceful close—beki, “must I” or “should I”—was bold, almost confrontational.

Those present soon realized, however, that this was no ordinary verse. Hidden within its thirty-one syllables lay multiple layers of kakekotoba—poetic puns and double meanings: karine (temporary bedding / cut reeds), hito yo (one night / the human world), and mi o tsukushi (to exhaust oneself / the guiding channel markers for sea routes). Far from being a courtesan’s song of fleeting passion, the poem carried a deeper, sharper edge.

2. The Poem of Defiance

What stunned the court was not simply the artistry of the verse, but its meaning. At first glance, it seemed to be a courtesan’s lament about a fleeting night of love in Naniwa Bay. But those trained in the art of kakekotoba—poetic wordplay—understood that this was no mere confession of passion.

Its deeper meaning, as the nobles realized, was unmistakable. In essence, the poem declared:

Even a courtesan of Naniwa may treasure a fleeting night of love for a lifetime.

But you, the high nobles of the court,

have forgotten centuries of loyalty to the Tenno and to the people

—discarded in a single night of strife, the Hōgen Rebellion.

Is it not your duty, as guardians of the realm,

to risk even your lives to preserve the peace and prosperity built by your forefathers?

The forceful ending, beki—“must I” or “should I”—was not the voice of fleeting romance but of moral outrage. The bettō, standing before the lords of the realm, accused them openly: power is not license, and betrayal of duty cannot be hidden beneath silence.

3. The Silent Court

The silence that followed was deafening. In the great hall where the most powerful men of the realm had gathered, no voice rose in answer to the poem. Their heads bowed, their eyes cast down; not one dared to speak.

For what reply could there be? She had invoked their ancestors, the sacred duty to the Tenno, and the betrayal embodied in the Hōgen Rebellion. To deny her was to deny truth itself. To admit her words was to confess their own cowardice.

Thus they did nothing. The might of the realm, the guardians of the court, were reduced to silence by thirty-one syllables. In that moment, the balance of dignity shifted: the voice of conscience stood above the weight of power.

4. The Political Turmoil: The Hōgen Rebellion

Behind the silence of that gathering lay a storm of politics and betrayal. The poem’s sting could not be understood without recalling the bitter history of the Hōgen Rebellion (1156), a conflict that had torn the imperial house and the Fujiwara clan apart.

The lady’s mistress, Kōkamon’in, had once been the Empress Consort of the Tenno Sutoku. Sutoku had ascended the throne as a child, married young, and by all accounts cherished his consort deeply. Yet their union produced no heir. This absence of a successor became a crisis—not for the Tenno alone, but for the Fujiwara clan, whose power rested on being the maternal relatives of the sovereign.

Fujiwara no Tadamichi, the Empress’s father, feared the rise of any child born from another consort outside his line. To protect his family’s supremacy, he forced Sutoku to abdicate and placed his younger brother, the boy-Emperor Konoe, on the throne. When Konoe died at just seventeen, another brother, Go-Shirakawa, was elevated as the 77th Tenno. Unlike a child sovereign, Go-Shirakawa was already twenty-nine—a man old enough to govern in his own right.

For Tadamichi and the Fujiwara, this was dangerous. A mature Tenno could not be ruled like a puppet. Worse, Sutoku—now an abdicated sovereign, an in (cloistered emperor)—technically ranked above even the regent in political status. If Sutoku and Go-Shirakawa had ever joined hands, the centuries-old dominance of the Fujiwara might have ended overnight.

Suspicion gnawed at Tadamichi. Though Sutoku outwardly withdrew from politics, devoting himself to poetry gatherings and a life of seeming detachment, the regent saw only scheming in his every gesture. Fear twisted perception into paranoia. Finally, he accused Sutoku of plotting rebellion. With Go-Shirakawa’s sanction, armed forces under Taira no Kiyomori and Minamoto no Yoshitomo attacked.

The result was the Hōgen Rebellion—a brief but bloody clash that marked the first time the court’s disputes were settled not by words but by swords. For the first time, the state had chosen violence as its final arbiter of justice.

From that moment, the precedent was set. Where once diplomacy and poetry had ruled, now soldiers in armor, blades bared, stalked the streets. The graceful Heian order gave way to an age of warriors.

5. A Woman’s Courage in an Age of War

By the time of the poetry gathering, the world had already changed. The court still held its refined rituals, but outside its walls the streets echoed with the clash of steel. Men in armor stalked the capital, and violence had become an accepted way to settle disputes. It was a dangerous age, one where speaking truth could cost a life.

For the bettō, the chief lady-in-waiting to Kōkamon’in, the stakes were even higher. By offering such a poem at an official gathering, she risked not only her own safety but also the honor—and perhaps the very life—of her mistress. Yet she chose to speak. Her words were not mere verses of art, but an act of defiance, a moral stand against the betrayal of duty.

One can imagine that before the gathering, she must have gone to Kōkamon’in and said:

“This poem, I offer on my own. Should there be blame, let it fall upon me alone. May no harm touch Your Grace.”

And one can also imagine the Empress, now a cloistered consort, nodding quietly, aware that to grant permission meant accepting the possibility of death—for both of them.

Thus the poem was not hers alone. It was the voice of two women bound by loyalty and love: the loyal attendant who stood in the line of danger, and the former empress who shared her resolve. In a world where swords had begun to decide the fate of nations, they chose instead to wield truth as their weapon.

6. Legacy of the Poem

The bettō’s verse was more than poetry. It was a mirror held up to the age, exposing betrayal at the heart of power. In thirty-one syllables, she demanded that the nobles remember their duty to the Tenno and to the people.

The silence of the court that day was itself testimony. They recognized the truth, even as they lacked the courage to acknowledge it aloud. Her words carried risk, but they also restored, if only for a moment, the moral weight of the realm.

In the centuries that followed, warriors would dominate the land, and swords would seem to drown out words. Yet the memory of such verses endured. They testified that even in times of turmoil, the spirit of justice could be spoken—if only by a single voice, standing unafraid.

7. Conclusion: Women, Power, and the Voice of Conscience

The story of the bettō at that poetry gathering is not only a tale of one brave woman. It is a reminder of what Japan has long held in its cultural heart: that dignity and conscience do not belong only to the powerful, but can be spoken by anyone—man or woman, noble or commoner.

In the West, it is often said that medieval women were silenced, confined to the margins of power. Yet in Japan, from the mythic age of Izanagi and Izanami onward, men and women were seen as partners, standing side by side. The voice of the bettō, rising in defiance before the lords of the court, was not an anomaly. It was an echo of that ancient equality, alive even in turbulent times.

What silenced the nobles that day was not only the sharpness of her rebuke, but the undeniability of her truth. She embodied what poetry in Japan had always been: not mere ornament, but a weapon of conscience, a way to confront power with the higher call of duty.

Eight centuries later, her words still speak to us. They remind us that power without responsibility is betrayal, that silence in the face of injustice is complicity, and that sometimes, it takes but a single voice—clear, fearless, and true—to bring the mighty to their knees.