(心のすれ違いと日本文学)

In Japanese literature, some of the most moving moments arise not from grand romances or battles, but from the smallest of gaps—the subtle misunderstandings between hearts. From the chrysanthemum fields of Nogiku no Haka to the timeless tales of the Kojiki and The Tale of Genji, these delicate misalignments reveal how men and women perceive, feel, and fail to fully grasp each other. Far from mere miscommunication, they are windows into a culture where empathy and “sensing the unspoken” (sasshi) have long been cherished as the essence of human connection.

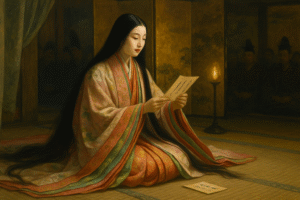

Black-and-white photograph of a young Japanese woman in a patterned kimono, holding wildflowers and looking down with a gentle smile, set against a blurred natural background.

1. Introduction: A Scene Among Wild Chrysanthemums

More than a century ago, novelist Itō Sachio captured a quiet yet unforgettable moment between two young cousins, Masao and Minako, in The Grave of the Wild Chrysanthemum (Nogiku no Haka). Minako, age seventeen, and Masao, age fifteen, had grown up together almost as siblings, though a deeper affection stirred beneath the surface.

On their way to the fields one day, they stopped to admire wild chrysanthemums blooming along the path.

“Masao-san, aren’t they beautiful? Will you give me half of them? I really do love wild chrysanthemums.”

“I’ve always loved them too. Do you like them as much as I do, Minako?”

“I’m practically a wild chrysanthemum reborn. When I see them, I feel a shiver of joy—so much that I even wonder at myself.”

“That explains it then. You remind me of the chrysanthemums themselves.”

Blushing, Minako pressed the flowers to her cheek, quietly overwhelmed. For her, Masao’s words meant far more than a passing remark. If she was like the chrysanthemum, and he loved chrysanthemums, then surely—surely—he loved her too.

But to Masao, these were separate thoughts: that chrysanthemums were lovely, and that Minako resembled them. He never intended it as a confession of love. And so, as Minako fell silent, lost in thought, Masao asked in confusion:

“What were you thinking just now, walking so intently?”

When she admitted that she was troubled by being older than him, he laughed it off. To him, it was simple: seventeen was seventeen, and in two years, he would be seventeen too. He could not grasp why she felt “ashamed.”

Thus, in this fleeting dialogue, we see the quiet birth of misunderstanding.

2. The Girl’s Heart vs. The Boy’s Words

For Minako, Masao’s words carried the thrill of an indirect confession. For Masao, they were only a passing comparison, innocent and unlinked to his hidden feelings. The girl’s heart ran ahead, connecting dots that the boy had not thought to join. The boy, though he loved her, lived within a mind that kept each thought separate.

Here lies the heart of the matter: women often intuitively weave emotions into a tapestry of meaning, while men may compartmentalize, holding each sentiment apart. The result is not indifference, but difference—a divergence in thought that creates distance even as love draws them near.

3. The Japanese Art of Subtle Misunderstanding

This quiet misalignment is not a flaw to be corrected but a theme deeply woven into Japanese literature. From the ancient myths of Izanagi and Izanami, whose union faltered over mismatched words, to the tragic love of Toyotama-hime and Yamasachi-hiko in the Kojiki, to the countless tangled relationships in The Tale of Genji, Japanese writers have long explored the subtle spaces where hearts miss each other.

What makes these stories enduring is not simply the romance itself, but the recognition that misunderstandings are part of what it means to be human. Readers nod in sympathy, not because the lovers succeed or fail in union, but because they recognize themselves in the hesitation, the silence, the glance misread.

4. Why Japan Could Treasure Subtle Feelings

Why did such delicate emotional misalignments become a theme in Japan, when they are nearly absent in Western and Chinese classics?

The answer lies in the fabric of society. In most of the world, for millennia, women were little more than possessions, their fates decided by conquest or exchange. In Greek myth, Pandora is a source of chaos; in Chinese history, beauties like Yang Guifei or Consort Yu are remembered only through the power they inspired in men. The inner heart of women was rarely the subject of art.

But in Japan, a different principle took root. From the earliest times, the Tenno—the sovereign—was not seen as a conqueror but as the spiritual axis of the nation. The Tenno declared the people to be Ōmitakara—“the great treasure.” This recognition, that the people themselves were the nation’s highest value, shaped an ethos where feelings mattered, where to notice and to honor the heart of another was itself a civic virtue.

It is for this reason that we use “Tenno” here rather than the more common translation “Emperor.” In the West, “Emperor” suggests absolute authority and domination. The Tenno, however, has historically stood not as a ruler in the Western sense, but as a symbol of unity and the sacred dignity of the people. To understand the literature of subtle feeling, one must also understand this unique cultural role.

5. The Difference with Western and Chinese Traditions

In the West, literature often focuses on whether love is fulfilled or thwarted—Romeo and Juliet united in death, Tess of the D’Urbervilles undone by fate, Nora leaving her doll’s house. The inner crosscurrents of thought and feeling are seldom the theme; women’s actions are often portrayed as mysterious, irrational, or fated.

In China, the portrayal is even starker: women appear as beautiful, tragic figures, their voices largely absent from the record.

Japan, by contrast, cultivated a literary culture where the tremors of the heart—hesitations, misread glances, words unspoken—became the very material of art. Here, the focus is not on conquest or loss, but on the gentle ache of almost-understanding.

6. A Culture of Sensing the Other

At the core of this tradition lies the Japanese value of sasshi—the ability to sense and infer another’s unspoken feelings. To live well was to notice, to feel, and to honor the subtle stirrings of another’s heart. This sensitivity extended from the highest court rituals to the humblest exchanges of daily life.

The enduring power of works like The Tale of Genji or Nogiku no Haka lies not only in their plots but in their invitation to readers: to remember that beneath every silence and every hesitation lies a heart struggling to be understood.

7. Toward an Age of the Heart

As the world moves beyond centuries of domination and fear, humanity stands at the threshold of a new possibility. The age of coercion may give way to an age of resonance—where people are not managed as pawns, but recognized as hearts capable of echoing one another.

Here, Japan’s tradition offers a gift. From the Tenno’s declaration that the people were “the great treasure,” to a literary culture that found profound meaning in the smallest misunderstandings of love, Japan shows us that to live well is not merely to survive or to conquer, but to notice another’s heart and to treat it with care.

If the twentieth century was an age of material might, the twenty-first may yet be shaped by gentleness—by the courage to notice, to feel, and to respond. The “age of the heart” will not be built by armies or decrees, but by the countless acts of understanding that bridge the subtle spaces between us.