There is a quiet song that echoes across centuries—gentle, solemn, and filled with grace.

This is “Kimi Ga Yo,” the national anthem of Japan.

Unlike anthems that praise power or glory, it offers a prayer: for peace, for life, and for a future where souls resonate together.

From its ancient poetic origins to its cross-cultural creation, “Kimi Ga Yo” reveals a vision of harmony that transcends time and borders.

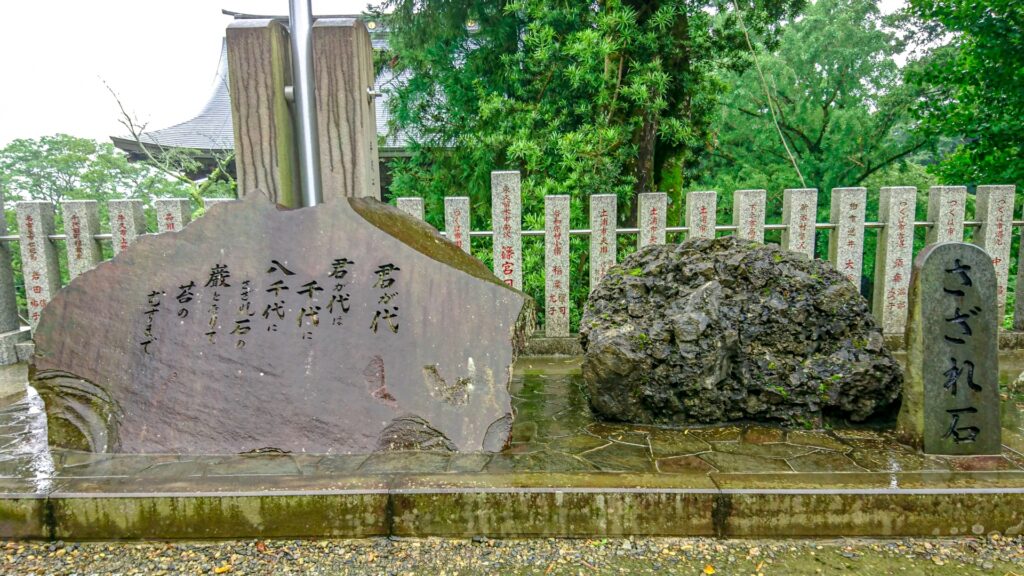

“Monument inscribed with ‘Kimi Ga Yo’ and the sacred ‘sazare-ishi,’ symbolizing the anthem’s prayer for enduring harmony.”

👉 The Whispering Song of a Nation

There is a quiet song that echoes through centuries—a song of harmony, hope, and timeless love. This is “Kimi Ga Yo,” the national anthem of Japan.

Unlike many anthems that celebrate triumph in war or national pride through power, “Kimi Ga Yo” speaks in a whisper—one that carries the ancient soul of a nation. Its melody is solemn and serene, and its lyrics, drawn from a thousand-year-old poem, are filled with mystery, tenderness, and reverence for life that endures.

But behind this seemingly simple song lies a rich and surprising history: one that weaves together East and West, poetry and politics, ancient myths and modern identity.

How did a short waka poem from the Heian era become a national anthem recognized around the world? And what do its elegant words truly mean?

In this article, we will explore the origins, evolution, and deeper meaning of “Kimi Ga Yo”—a national anthem like no other.

👉 What Makes “Kimi Ga Yo” So Unique?

To many outside Japan, “Kimi Ga Yo” may seem puzzling.

It is one of the shortest national anthems in the world—just 32 syllables long—and it makes no direct mention of the country’s name, its people, or even a specific historical event.

What is this anthem truly about?

Some interpret it as a song of imperial reverence, others see it as a timeless prayer for peace and continuity.

Its slow, solemn melody and poetic lyrics stand in stark contrast to the stirring marches and triumphant tones of many Western anthems.

Is it a relic of the past, or a window into a uniquely Japanese worldview?

Moreover, how did such a gentle, almost mystical verse come to represent an entire nation?

Why was it chosen, and how has its meaning been shaped—sometimes misunderstood—across generations?

These questions invite us to look deeper into the story of “Kimi Ga Yo,” beyond assumptions and into the heart of its cultural and spiritual origins.

👉 A Global Anthem Born in Japan

The story of “Kimi Ga Yo” does not begin with a Japanese composer, but with a British military bandmaster named John William Fenton.

In the early Meiji era, Fenton was stationed in Yokohama as the band leader for the British legation. He began training young men from the Satsuma domain in Western-style brass music—forming Japan’s very first military band, the Satsuma Military Band.

In October 1872, Fenton spoke with a young Japanese officer—Ōyama Iwao—who would later become one of Japan’s most revered statesmen.

Fenton suggested that the new Meiji government adopt a national anthem for formal state ceremonies, as was common in Western nations.

Ōyama agreed and proposed the lyrics of a song he personally favored, drawn from a Satsuma biwa performance—a style of narrative ballad accompanied by a Japanese lute, traditionally sung in samurai households.

The piece included a long and elegant celebratory verse, one portion of which later became the lyrics of the anthem. The full poem reads:

Medetaya na / Kimi ga megumi wa hisakata no / Hikari nodokeki haru no hi ni

Furō no mon o tachi idete / Yomo no keshiki o nagamureba

Mine no komatsu ni hinazuru sumite / Tani no ogawa ni kame asobu

Kimi ga yo wa / Chiyo ni yachiyo ni / Sazare ishi / Iwao to narite / Koke no musu made…

Here is a poetic interpretation of the full passage:

“How blessed we are—your gracious reign shines like the eternal spring sunlight, gentle and warm.

Emerging from the gate of immortality, as we gaze upon the scenery in every direction,

we see young cranes nesting in the pines upon the mountain peaks,

and turtles playing in the clear stream of the valley.”

This imagery paints a vision of peaceful and eternal harmony, in which the ruler’s benevolence extends softly across the land.

Cranes and turtles—longstanding symbols of longevity in Japanese culture—emphasize the prayer for enduring life and grace.

From this extended verse, only the final lines beginning with “Kimi ga yo wa…” were selected as the anthem’s official lyrics.

Their meaning is essentially a heartfelt wish:

“May your reign continue for a thousand, eight thousand generations, until pebbles grow into boulders and are covered in moss.”

Fenton composed a melody for these lines, but it was not well received.

The tune, with its Irish folk flavor, was considered too foreign and lacked the dignified tone expected of a national anthem in Japan.

Recognizing this, in 1876, the Japanese Navy submitted a formal request to revise the anthem.

The petition emphasized the importance of an anthem that could reflect Japan’s identity and national dignity, especially in diplomatic ceremonies.

To Fenton’s credit, he did not oppose the revision. On the contrary, he supported it—perhaps out of the deep respect he had developed for Japanese culture and spirit during his years of residence.

In 1880, the Meiji government officially commissioned the creation of a new composition.

A court musician, Oku Yoshiisa, composed the new melody. This was further refined by Hayashi Hiromori, a master of gagaku (ancient court music).

Finally, Franz Eckert, a German music teacher then residing in Japan, orchestrated the piece in a solemn Western style, adding the grandeur expected of a national anthem.

The result was a truly extraordinary collaboration across cultures and continents:

a British proposal, Japanese poetic tradition and musical refinement, and German orchestration.

The anthem’s melody, in other words, is the product of peaceful international cooperation—a symbol not of conquest, but of shared respect and artistic unity.

👉 The Sacred Meaning of “Kimi” and the Song of Life

At the heart of “Kimi Ga Yo” lies a word both simple and profound: kimi, often translated as “you” or “my lord.”

But who, or what, is “kimi”?

Historically, the “kimi” referred to the emperor—a symbol of unity and continuity in Japanese society.

But over time, the word took on broader meaning. Like a prism reflecting many colors, kimi could signify a beloved person, a community, or even the spiritual ideal of harmony itself.

It is not just a ruler being celebrated—it is the continuity of life, of generations, of something greater than oneself.

Interestingly, the original poem in the Kokin Wakashū—compiled in the year 905—began with the phrase “Waga kimi wa” (“My lord is…”), clearly referencing the sovereign.

But in later anthologies such as the Shinpen Waka Shū and the Wakan Rōeishū, the wording changes to “Kimi ga yo wa”—a subtle but powerful shift.

This suggests that the phrase had already become widely known and sung in various forms, indicating its deep-rooted presence in the people’s cultural life.

In ancient Japanese, each syllable held spiritual resonance.

The word kimi itself carries layered meaning:

• ki represents generative energy, brightness, or the male principle—echoing the deity Izanagi.

• mi symbolizes essence, purity, and the female principle—reflecting Izanami.

Together, ki and mi form the sacred pair from which life begins.

Thus, kimi is not just a person, but a metaphysical unity—both masculine and feminine, spirit and matter, radiating life across time.

From this perspective, “Kimi ga yo” is a wish not only for a ruler’s reign to endure, but for the sacred bond of life itself to thrive—through generations, through harmony, through nature.

It is a prayer for continuity that transcends borders, epochs, and ideologies.

The image of pebbles becoming boulders, then covered with moss, is not about power—it is about patience, rootedness, and the beauty of things that endure quietly.

It reflects a worldview in which permanence is not asserted by force, but nurtured by time, humility, and connection.

Unlike many national anthems that celebrate the glory of nations through war or conquest, “Kimi Ga Yo” offers a vision of peace, reverence, and eternal life.

It is both personal and universal—a song of love that spans centuries, and a mirror of Japan’s spirit at its most serene and profound.

👉 A Quiet Blessing for All Generations

“Kimi Ga Yo” is more than a national anthem.

It is a living poem—a song of harmony that connects the past with the present, and echoes far into the future.

Born from the fusion of Japanese spirit, British initiative, and German artistry, its creation itself symbolizes the beauty of cultural cooperation over conflict.

Its lyrics, drawn from ancient poetry, do not shout of conquest or pride.

Instead, they whisper of love, longevity, and the sacred bond of life—a bond of souls resonating together, so often overlooked in the modern world, yet deeply needed.

In a time when so many voices cry out for division or dominance, “Kimi Ga Yo” offers a quiet alternative:

A song that does not command, but blesses.

A song that reminds us that greatness is not in how loudly we sing of power, but in how deeply we sing of peace.

May we continue to listen to that gentle voice across the centuries,

and may its spirit guide us—not just as Japanese, but as fellow travelers on this shared journey of life.

May the spirit carried in this anthem reach hearts all around the world.