In most societies throughout history, social order has been maintained through systems of domination, authority, and force. But Japan quietly presents a different path—one where harmony arises not from control, but from reverence. At the heart of this system is the TENNOU, a figure who holds no political power, yet remains central to the nation’s identity. This article explores how Japan’s “powerless sovereign” has helped shape a society defined not by fear, but by mutual respect—and what that might mean for the future of humanity.

Shishinden, the main ceremonial hall of the Kyoto Imperial Palace—where the presence of the TENNOU has long symbolized cultural continuity rather than political rule.

1 Introduction

A Nation Without Rule: The Hidden Strength Behind Japan’s Harmony

In a world where social order has long been shaped by domination and submission, Japan offers a quiet yet deeply meaningful alternative. This very difference is what has allowed Japan to preserve its national identity for over two thousand years. Many foreign visitors to Japan often express the same impressions: Japanese people are kind, the streets are clean, and public safety is remarkably high.

Take, for example, a first-time visitor riding the Shinkansen. Beyond the smooth ride and quiet comfort, what often surprises them most is seeing small kiosk shops on station platforms with goods displayed even on the outer walls—completely unattended—and yet, theft is virtually nonexistent.

Why is Japan like this? The answer lies in the presence of the TENNOU—not as a powerful ruler, but as a figure without political authority.

Traditionally, the Japanese head of state has been translated into English as "Emperor." However, this is in fact a mistranslation. The term "Emperor" comes from the Latin "imperator," originally meaning a commanding general, and later referring to the highest sovereign ruler. In contrast, the Japanese TENNOU does not possess political power, nor does he issue commands. His role is not that of domination, but of presence—much like the revered patriarch of a large family. For many Japanese, the TENNOU is felt as the symbolic grandfather of the nation, embodying cultural continuity and unity.

It is precisely this absence of political power that reveals a unique cultural strength. Social harmony in Japan is not built on control, but on reverence. At the heart of Japan’s gentleness lies a profound worldview: that people are not subjects to be ruled, but treasures to be protected.

2 Problem or Question

If Not Power, Then What? Rethinking the Foundation of Social Order

So why has such a unique cultural system developed in Japan—and why has it lasted so long?

In many countries, “order” has traditionally meant rule by force. Political leaders create laws, enforce them through military and police power, and maintain social stability through top-down control. The people are viewed as subjects to be governed, and obeying those in power is taken as a given.

In contrast, Japan has long upheld a national identity in which every citizen is considered “Ōmitakara”—“Great Treasures"—by the highest symbolic figure of the nation: the TENNOU. This cultural foundation has shaped a collective understanding that, regardless of rank or authority, all individuals are fundamentally equal in their humanity.

This sense of dignity gives rise to a classic Japanese spirit, especially among ordinary people, who might say:

“Sure, you may be an important official,

but we common folk have our own worth, too!

Haven’t you heard the saying?

Even a tiny insect has a soul half as great as yours!After all,

we’re the TENNOU’s Ōmitakara—his sacred treasures!”

In other words, in Japan, the source of social order is not power—it is respect.

But how did such values take root in Japan in the first place?And what foundational principles made it possible for this worldview to endure?

3 Facts and Observations

A Moral Architecture: How the TENNOU Shaped Japan’s Unique Social System

Since ancient times, Japan has upheld a remarkably unique system in which the TENNOU stands as the highest authority in the nation—but without holding political power. Instead of ruling over the people, the TENNOU’s role has been to Shirasu —to “listen to the voices of the people” and convey the will of the gods to them.

The TENNOU has traditionally served as a bridge between the divine and the human. His words were regarded as the words of the gods, and the voice of the people was seen as something that should reach the TENNOU as a reflection of divine will. Within this sacred framework, the people were not considered mere subjects, but rather Ōmitakara—“Great Treasures” of the nation.

Of course, any functioning society requires some form of hierarchy and division of roles. Japan has its own version of the concept of “rule.” But here’s the twist: those in positions of authority are understood to be subordinates of the TENNOU. Which leads to a fascinating reality:

The people under a ruler’s control are not his possessions, but the cherished treasures of his superior—the TENNOU.

It’s as if a well-paid executive excitedly reports to work, only to discover that all the employees under him are actually the family members of the company’s largest shareholder.

In this context, the primary duty of those granted power is not to dominate, but to ensure that the TENNOU’s treasures—his people—live in peace, safety, and prosperity. In old Japanese, this form of benevolent stewardship is called Ushihaku. While the word originally implies ownership, it is framed within a system where the true “top” is not the owner of power, but the TENNOU who does not wield it. The authority to rule is thus embedded within the greater principle of Shirasu—a moral order that defines the sacred status of the people.

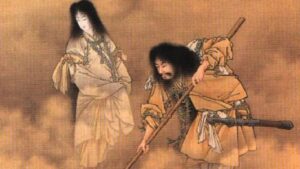

The same applies to the warrior class. Samurai possessed the means of violence, but that force existed solely to protect the people—the treasures entrusted to their lords by the TENNOU. A samurai’s duty was to lay down his life, if needed, to safeguard those lives. In this context, Gi—the core virtue of Bushidō—meant protecting the happiness and peace of the people.

Thus, the structure of Japanese order was not “God → TENNOU → subjects → people,” but rather:

“God → TENNOU → people → the retainers and warriors who serve and support them.”

In this framework, political power was delegated to the TENNOU’s subordinates, but always accompanied by sacred responsibility. That is why, in Japan, the logic of “the strong can do whatever they want” never became the foundation of social order.

4 Your Thoughts and Interpretation

Beyond Hierarchy: Respect, Humility, and the Spirit of Bushidō

When we reflect on how this unique social structure has shaped the mindset of the Japanese people, a number of fascinating insights emerge.

First, the awareness that all citizens are considered Ōmitakara—“Great Treasures”—under the care of the TENNOU has nurtured a deep cultural sense of equality and mutual respect. This is not merely a political or legal construct, but a spiritual foundation that supports the belief that “everyone is different, and that’s perfectly okay.” It reflects a worldview rooted not in uniformity, but in the inherent dignity of each individual.

Second, the idea that even rulers are merely subordinates of the TENNOU has cultivated a cultural expectation of humility and responsibility among those in power. In Japan, it has traditionally been seen as virtuous for those in higher positions to act with self-discipline and a spirit of service to others. This is reflected most clearly in the ethical code of Bushidō, where the virtue of Gi—righteousness—is understood as the willingness to sacrifice oneself for the wellbeing of the people.

Moreover, everyday behaviors often admired in Japanese society—such as kindness, social order, and attentiveness to others in public spaces—can also be traced back to this cultural structure. These values are not enforced through top-down moral education, but rather arise organically through daily life within a social framework that prizes respect, harmony, and collective well-being.

In this way, the TENNOU’s very lack of political power has become his greatest strength: by standing outside the structures of control, he serves as a moral and emotional anchor for the people—a source of empathy, unity, and quiet strength.

5 Conclusion

Empathy Over Power: What Japan Can Teach the World About Order and Humanity

In today’s world, many nations maintain order through power, control, and efficiency. But Japan has long embraced a completely different model—one rooted in reverence and resonance rather than domination. At the center of this ancient yet enduring structure stands the TENNOU, a figure who holds no political power.

The TENNOU does not rule the people, but cherishes them as Ōmitakara—“Great Treasures.” He listens to their voices and serves as a bridge between the gods and the people. In this role, what exists is not control, but empathy. And through that empathy, hearts resonate—shaking and echoing together in harmony. It is through this resonance that the Japanese have lived their history: not in conflict, but in quiet connection. This unique spiritual framework has given the people both pride and peace of mind, fostering a social environment where hierarchy can coexist with a deep sense of human equality.

This is why kindness and order in Japan often arise not from imposed discipline, but from within. These qualities are not simply taught—they are felt, absorbed from the atmosphere of a culture shaped by mutual respect.

At a time when the world is increasingly fractured by division and discord, perhaps it is time to re-examine Japan’s model—an ancient path that may offer new hope.

To recognize that every person is someone’s treasure.

To believe that order comes not from force, but from respect.

These may be the very keys to the future of a more compassionate civilization.