In an age that celebrates success and comfort, the story of Tennou Nintoku offers a striking contrast.

He did not seek fame or display, but instead took on hardship to carry the future of the nation and stand by the poor.

Far from being a mere feel-good tale, his story speaks to a form of leadership rooted in Japanese culture—built on empathy, restraint, and the presence that is not seen, but deeply felt.

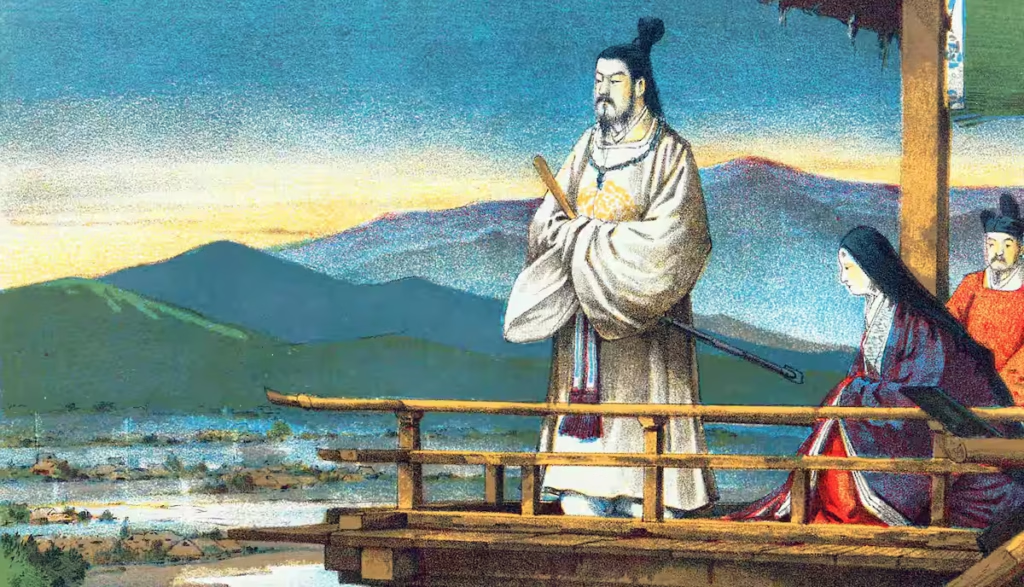

A painting depicting the legend of Emperor Nintoku and “the people’s hearths”(from the Digital Collection of the National Diet Library of Japan)

🌸 What Does the “Smoke from the People’s Stoves” Really Mean?

The smoke rising from a household stove is more than just a plume in the air.

It is a sign that a family is gathered around a shared meal, that life continues, and that the rhythms of daily living are intact.

The ancient story of Tennou Nintoku—the Japanese sovereign who, upon seeing no smoke rising from his people’s homes, lifted all taxes for three years—is not merely a heartwarming legend.

It is a profound cultural memory that reflects Japan’s deep-rooted ethical sensibility and capacity for empathy.

In this article, I refer to him not as “the Emperor,” but as “THE TENNOU.”

This is intentional.

In English, “Emperor” implies the supreme ruler among kings—a wielder of the highest power.

But in Japan, the Tennou is not a ruler in the Western sense.

He is not a power-holder, but the highest moral authority of the nation—above kings, above governance, yet not directly exercising control.

This Tennou does not appear before his ministers or the people.

He remains behind a bamboo screen called a misu, unseen yet undoubtedly present.

No one can discern his expression—whether he is pleased, dissatisfied, or contemplative—because he does not reveal it.

And yet, he is there.

Because of this, the ministers and lords are compelled to govern with utmost sincerity and dedication to the people—who are considered Oh-Mitakara, the “Great Treasures” of the Tennou.

Here lies a foundational idea of Japanese civilization: governance through resonance, not domination; trust, not command.

And perhaps, in this ancient tale, Tennou Nintoku offers us a timeless question—one that echoes across centuries—about how leadership should respond to poverty, division, and the abuse of power.

🌿 The Story of the Smoke and the Emperor

In the fourth year of his reign, Emperor Nintoku looked out from his palace at Takatsu in Naniwa and noticed something troubling. There was no smoke rising from the household stoves.

“No smoke from the people’s stoves… Could it be that they are so poor they have nothing to cook? If the capital is like this, the countryside must be suffering even more,” he thought.

Deeply moved, Nintoku gave a rare command—through the veil behind which he resided—to his ministers:

“For the next three years, suspend all taxes.”

Such a direct order from behind the imperial curtain was almost unheard of, and for the ministers, it became an absolute priority.

Three years passed. Once again, the Emperor gazed over the capital. This time, smoke was rising vigorously from every home. With joy, he turned to the Empress and said:

“I am now rich. This is a joyful thing.”

The Empress, puzzled, replied,

“How can you say that? The palace fences are broken and the roof still leaks…”

Smiling gently, the Emperor responded:

“My dear Empress, listen well. The purpose of governance is to care first and foremost for the people. If the people are now prosperous, then I too am rich.”

Thanks to this act of compassion, the people’s lives improved. The Nihon Shoki, one of Japan’s oldest historical chronicles, records that “not even a forgotten item left on the road was taken,” so orderly had society become.

Ministers approached the Emperor and said:

“The people have regained their wealth, but the palace remains in ruins. Please allow us to collect taxes and repair the palace. If not, we fear we will face divine punishment.”

Yet the Emperor declined and chose to continue the tax exemption for another three years.

In total, six years passed. Only then did Emperor Nintoku permit the collection of taxes and the restoration of the palace. The Nihon Shoki records what happened next:

“Without being told, the people brought timber, carried it on their backs, and worked day and night, competing to give their strength. In no time, the palace was completely restored. Therefore, even today, he is revered as a Sage Emperor.”

Out of deep gratitude, the people undertook the repairs voluntarily. No one forced them. They worked tirelessly, transporting materials and building as if in friendly competition. As a result, the palace was quickly restored.

But Emperor Nintoku had a greater plan.

Once the people’s prosperity had recovered, he led a vast civil engineering project with his ministers. Through these works, the once-barren lands between Osaka and Nara were transformed into fertile rice fields. The abundant harvests produced enough rice to be stored for two full years, creating a stable food reserve.

Japan is a country often hit by natural disasters—earthquakes, typhoons, floods. But thanks to these food reserves, Emperor Nintoku established a system where no one would go hungry, even in times of hardship.

And notably, these public works began only after the period of tax relief. From a time of famine and hardship, the Emperor took six years to restore the economy of both the people and the nation. Only then did he initiate full-scale food production and the construction of large granaries.

This was the 4th century—a time when much of the world still lived in fear and fought over food.

The strong often took from the weak.

But Nintoku Tenno envisioned a society where no one would suffer from hunger. By building a structure of compassion, stability, and shared well-being, he ensured peace and security for all people—whom he cherished as Ohomitakara, the precious treasures of the realm.

📝 A Vision of Governance Rooted in Ethics and Empathy

Interestingly, in ancient Japan, the Tennou—the sovereign—did not show himself, not even to the highest officials of the government, let alone to ordinary people.

He always remained behind a bamboo screen called a misu, a practice deeply symbolic in Japanese culture.

Why such secrecy?

It is because each person holds a different ideal of what a great leader should be.

Some may value strength, others kindness or wisdom.

By not revealing his physical form, the Tennou allowed each subject to imagine their own ideal of sovereign leadership within their hearts.

He became not a visible ruler, but a felt presence—an embodiment of virtue, empathy, and harmony.

In this way, the Tennou stood not as a wielder of power, but as a moral compass for the people.

The citizens were not treated as mere “subjects,” but rather honored as Oho-Mitakara—“Great Treasures.”

Even the highest ministers, despite their authority, could not discern from behind the misu whether the Tennou was pleased or displeased.

He stood above worldly desires and served as the nation’s ethical north star.

Because of this moral structure, ministers had no choice but to govern sincerely, placing the well-being of the people first.

It was within this profound cultural framework that Emperor Nintoku issued the command to suspend taxes for three years.

And when such a divine directive was delivered from behind the sacred screen, all the court officials could do was bow deeply in reverence.

This story is not merely about tax exemption.

It illustrates a deeper truth: that in Japan, invisible virtue moves a nation more powerfully than visible authority.

It is a philosophy of leadership where ethics, not dominance, hold the highest sway.

🌸 The Invisible Sovereign — A Leader Felt, Not Seen

The story of Emperor Nintoku and the “smoke from the people’s stoves” is not merely a tale of ideal governance.

It reflects a deeply rooted political philosophy unique to ancient Japan: governance through resonance.

In those early times, the Tennou would not appear publicly.

He remained behind a bamboo screen—misu—not to conceal himself, but to allow something deeper to emerge.

The belief was this: each person carries within them their own ideal image of a sovereign.

By not showing his face, the Tennou allowed the people to imagine him in their hearts as the leader they personally desired.

This subtle and compassionate structure of empathy nurtured trust and, in time, created a stable society.

The Tennou governed not by commanding, but by being felt.

His presence inspired not fear, but harmony.

Even Emperor Nintoku’s famous three-year tax exemption should not be seen as a mere political decision,

but rather understood within the cultural context of kakurimi—the sacred “hiddenness” I wrote about in yesterday’s article on this blog.

Emperor Nintoku’s choices in the 4th century became the ethical foundation upon which, centuries later, the samurai would refine the spiritual code of Japanese leadership.

From this, a civilization emerged—one where true authority flows not from power, but from moral presence and shared resonance.