What does it mean to die with dignity?

In the final days of Takamatsu Castle’s siege, the samurai lord Shimizu Muneharu stepped into a boat, performed a sacred dance, and calmly took his life. But this was no mere surrender—it was a spiritual act rooted in centuries of Japanese belief about the soul, rebirth, and responsibility.

Through the lens of a wartime school textbook, this article explores the profound meaning behind Muneharu’s final gesture—and how even in death, he became a symbol of grace, duty, and eternal becoming.

1 A Quiet Lesson in Dignity: What a Wartime Textbook Taught Children

In the midst of wartime Japan, a sixth-grade language textbook introduced a powerful story—one that quietly speaks to the dignity of life and the nobility of self-sacrifice. It is the tale of Shimizu Muneharu, the valiant lord of Takamatsu Castle, and his final moments during Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s siege. Titled “A Single Gesture of Dance,” this story, taken from a real historical event, was more than just a lesson in reading or writing. It was a lesson in humanity.

But why did Lord Muneharu, facing imminent death, choose to perform a sacred dance—Kusemai from the Seiganji Temple—before his ritual suicide? And why was such a solemn tale taught to children during an era known for its militarism? These questions lead us into a deeper inquiry—not only into the story itself, but into the values and educational philosophy that shaped young minds in that time.

2 Why Was This Story Told to Children? Loyalty, Death, and Meaning

Modern Japanese education is often criticized for focusing too narrowly on surface-level comprehension—“What does ‘this’ refer to in the sentence?”—rather than nurturing thoughtful reflection. In contrast, the wartime classroom, far from being solely about producing obedient soldiers, frequently encouraged students to think deeply and engage in spirited discussion. What, then, was the purpose of sharing stories like that of Lord Muneharu with young children?

Was it to glorify loyalty? To prepare them for death? Or was it something more profound: to help them grapple with the meaning of honor, the burden of leadership, and the quiet power of personal choice? And perhaps more importantly, what can this story teach us today—about life, education, and the soul of a nation?

3 Siege, Sacrifice, and the Final Dance: The True Story of Takamatsu Castle

In the tenth year of Tenshō (1582), during Japan’s turbulent Sengoku period, Toyotomi Hideyoshi—then a leading general under Oda Nobunaga—was ordered to subdue the Mōri clan in western Japan as part of Nobunaga’s campaign for national unification. Takamatsu Castle in Bitchū Province became the final stronghold resisting Hideyoshi’s advance. Its lord, Shimizu Muneharu, was widely respected for his combination of wisdom and courage. The castle, surrounded by swamplands and accessible only through two narrow routes, was considered nearly impregnable. Despite relentless attacks, Muneharu and his 5,000 devoted troops held their ground.

Finding a direct assault unfeasible, Hideyoshi accepted a daring strategy proposed by his advisor Kuroda Yoshitaka: to flood the castle. A massive embankment was built, and the waters of the Ashimori River were diverted. Soon, the surrounding rice fields turned into a lake, isolating the fortress. As the water rose, Muneharu saw that the castle’s fall was imminent. He could not bear to see his men—many of whom were women and children—drown, nor could he bring himself to betray his lord, Mōri Terumoto, by surrendering.

At one point, the Mōri side sought peace. Negotiations were conducted through the Buddhist monk Ankokuji Ekei, with the Mōri offering to cede five provinces in exchange for peace. Hideyoshi, however, refused. Then, a shocking event occurred: Oda Nobunaga, Hideyoshi’s lord, was assassinated in the Honno-ji Incident. Realizing the urgency of the situation, Hideyoshi changed course and agreed to peace—but only on one condition: that Shimizu Muneharu take his own life in exchange for sparing the castle’s defenders.

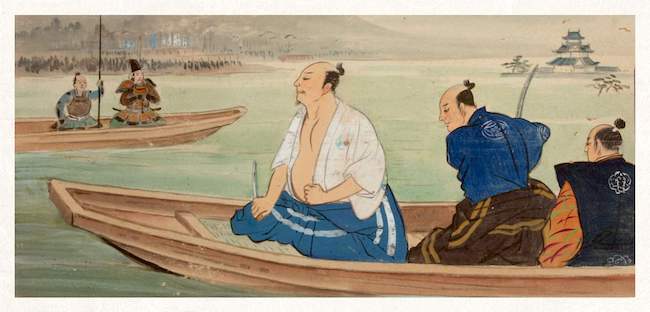

Muneharu agreed without hesitation. That night, one of his loyal retainers, Mukai Haruyoshi, committed ritual suicide before him, demonstrating profound loyalty. The next morning, Muneharu dressed in formal attire, boarded a boat with five companions, and rowed to meet Hideyoshi’s emissaries. After exchanging respectful words and sharing a final drink, Muneharu stood and performed the sacred kusemai dance from Seiganji Temple. Then, with calm grace, he recited a death poem and carried out seppuku. His retainers followed.

This story was taught to schoolchildren not merely as a historical account but as a vivid lesson in moral integrity—loyalty, self-sacrifice, and quiet strength. It also introduced them to traditional performing arts and the Buddhist ideals of salvation and compassion.

4 More Than a Death: The Kusemai of Seiganji and the Soul’s Journey

Why did Shimizu Muneharu choose to perform the kusemai of Seiganji Temple—a sacred, poetic dance—just before taking his own life?

This was not a spontaneous gesture, nor a mere cultural formality. The kusemai he performed comes from a Noh play titled “Seiganji,” based on a profound spiritual encounter between two historical figures: Ippen, a wandering monk and founder of the Ji sect of Pure Land Buddhism in the Kamakura period, and the spirit of Izumi Shikibu, a famed female poet of the Heian era. In the story, Ippen distributes sacred amulets while preaching at Seiganji Temple. A beautiful woman appears, questioning the inscription on the amulets—“Sixty million souls guaranteed salvation”—wondering if salvation is numerically limited.

Ippen explains gently that the phrase is symbolic: the light of Amida Buddha knows no bounds and embraces all beings equally. The woman, moved by this truth, reveals herself to be the spirit of Izumi Shikibu, buried at the temple. She dances, and her soul is released, transforming the temple into a realm of radiant fragrance and light.

This is the very dance that Muneharu chose to perform at the threshold of death.

In that moment, Muneharu was not merely a military leader submitting to political circumstances. He was manifesting a deeper spiritual reality: that death is not an end, but a transition. By choosing the kusemai of Seiganji, he aligned his final act with a sacred narrative of redemption and transcendence. His death became not just an act of resignation, but of prayer—an offering to the divine.

In Japan, death has never simply meant the cessation of life. Since the distant Jōmon era, the Japanese have held the belief that the soul is the true self, while the body is merely a vessel. The soul is like an egg, destined to become a deity. It is reborn into this world again and again, growing and strengthening through trials shared with others who also walk the path of rebirth. Life itself is a field for cultivating the soul.

From this perspective, Muneharu’s death did not signify finality. It carried a quiet message: “I will go ahead to the next world.” It was a gesture of responsibility and remorse—not for personal failure, but for the fate of his people and his country. By enduring the pain of self-disembowelment, he purified his regret. In doing so, he planted the vow that in the next life, he would return stronger and protect them more fully.

And so, his death was not a defeat.

It was an offering to the gods.

Through his dance, his poem, and his dignified passing, Shimizu Muneharu became not a tragic figure, but a spiritual bridge—reminding us that the soul lives on, and that within each death lies the seed of eternal becoming.

5 To Choose Beauty Even in Defeat: What Muneharu Still Teaches Us Today

The story of Shimizu Muneharu is not just a tale of loyalty or heroism—it is a mirror reflecting the spiritual and cultural soul of Japan. His final act, the kusemai upon the water, reveals a worldview in which death is neither a failure nor an end, but a step in the ongoing journey of the soul. Rooted in a belief that the spirit transcends the body, and that life is but a chapter in a greater unfolding, this understanding has endured in Japan since the Jōmon era.

Such stories were once taught to children—not to glorify war, but to teach them how to live with dignity, how to die with meaning, and how to carry the weight of responsibility for others. They were lessons in empathy, resolve, and a profound sense of inner maturity. Education was not merely about knowledge; it was about cultivating character, spirit, and a shared understanding of life’s sacredness.

Today, in a world where efficiency often replaces depth, and where argument too easily becomes noise, we are called to remember these deeper values. We are reminded that the purpose of learning is not only to think, but to feel, to respect, and to grow into beings capable of both reason and reverence.

The quiet dignity of Muneharu’s final dance offers us more than history—it offers us guidance.

It tells us that even in the face of defeat, we can choose beauty.

Even in death, we can choose to become light.

And even as individuals, we can live—and die—as part of something eternal.