In an age where quick profit and personal gain often take center stage, the timeless story of Katō Kiyomasa reminds us of a deeper kind of strength—one rooted in sincerity, duty, and keeping one’s word. Once taught to schoolchildren across Japan in the prewar Shūshinsho (Moral Instruction Book), Kiyomasa’s tale offers a powerful lesson for the modern world: that true honor lives not in grand victories, but in the quiet resolve to uphold shingi—faith and justice—even when no one is watching.

🌿1 “A Warrior of Integrity in Japan’s Moral Textbook” — What the Story of Kiyomasa Still Teaches Us Today

Before World War II, Japanese elementary schools used a textbook called Shūshinsho (Moral Instruction Book) to teach children about ethics and character.

Among its pages was the story of Katō Kiyomasa, a samurai celebrated not just for his strength, but for his unwavering shingi—a word that combines trust, honor, and keeping one’s word.

Through this episode, we are reminded of values we may be losing in the modern age: sincerity and the resolve to keep promises.

Kiyomasa’s story invites us to reflect once more on the quiet strength of being honest, faithful, and true to one’s word.

🌿 2 Why Now—Why Shingi Still Matters Today?

Why does the name of Katō Kiyomasa still resonate in the hearts of so many Japanese people, centuries after his time?

The answer lies not only in his strength as a warrior, but in something deeper: a value known in Japanese as shingi (信義).

This term, often translated as “faithfulness and honor,” carries a richer cultural meaning.

Shin (信) means trust or sincerity; gi (義) signifies duty, justice, and moral righteousness.

Together, they form a moral compass that guided not only individual actions, but the very foundation of leadership and loyalty in feudal Japan.

Today, we live in a world increasingly dominated by self-interest—what some critics in Japan have described as the age of “ima dake, kane dake, jibun dake” (今だけ・カネだけ・自分だけ):

“Only now, only money, only myself.”

In such a world, the spirit of shingi is in danger of being forgotten.

So what exactly is shingi, and why does it matter?

To explore this, let us return to the story once taught to fifth-grade children in Japan’s prewar moral instruction book, the Shūshinsho.

Through the conduct of Kiyomasa, we are invited to reconsider a virtue that may feel distant, but remains vital to human dignity.

🌿 3 The Lesson of Shingi — Katō Kiyomasa’s Loyalty in the Moral Textbook

“Shingi: The Duty to Act When Honor Demands It”

Katō Kiyomasa, like his lord Toyotomi Hideyoshi, was born in the province of Owari (in present-day Aichi Prefecture).

He lost his father at the age of three and was raised by his mother. As she was a cousin of Hideyoshi’s mother, young Kiyomasa was eventually taken into Hideyoshi’s household and brought up under his protection.

At age fifteen, Kiyomasa entered Hideyoshi’s service as a samurai. He distinguished himself in many battles and steadily rose through the ranks. In time, he became a powerful warlord, entrusted with the domain of Higo (in modern-day Kumamoto Prefecture) and known as one of Hideyoshi’s most trusted generals.

When Hideyoshi succeeded in pacifying a fractured Japan, he turned his ambitions outward—to conquer Ming China. In pursuit of this grand vision, he launched a military campaign through the Korean Peninsula.

Kiyomasa was sent as one of the lead generals.

Among Kiyomasa’s closest friends was Asano Nagamasa, whose son Yoshinaga also joined the campaign and fought bravely in Korea.

At one point, while defending the fortress of Ulsan, young Yoshinaga came under fierce attack by a massive Ming army.

His troops were outnumbered, and the siege grew desperate.

In urgent need of reinforcements, Yoshinaga sent word to Kiyomasa.

But Kiyomasa had only a small force—far too few to stand against the enemy’s overwhelming numbers.

Still, upon receiving the plea, Kiyomasa declared:

“Before leaving for the front, Yoshinaga’s father Nagamasa entrusted me with his son’s safety.

I gave my word.

If I do not rush to his aid, I cannot face Nagamasa again.”

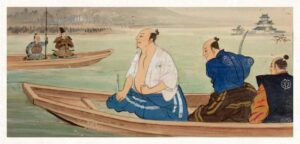

Despite the danger, Kiyomasa immediately set sail with 500 mounted troops aboard just 20 vessels.

Wearing his signature silver helmet and wielding a long spear, he stood at the prow of the lead ship, personally commanding the charge.

Charging head-on into a sea of enemy ships, Kiyomasa scattered their fleet and broke through the encirclement to reach Ulsan Fortress.

There, he joined Yoshinaga in a fierce defense.

Though vastly outnumbered, the two commanders held their ground, inflicting heavy losses on the enemy.

Eventually, their supplies dwindled—food ran out, and even water became scarce.

But they endured.

And in the end—they prevailed.

This is the kind of story that once graced Japan’s elementary moral textbooks, teaching children that honor is not merely about what one believes, but what one does when it matters most.

As the old saying goes:

“Gi wo mite sezaruhwa, yū naki nari.”

To see what is right and not do it is to lack courage.

🌸 4 The Power of Makoto and Kotowari — What “Shingi” Truly Means in Japan

While Katō Kiyomasa is remembered for his military might, it is his shingi—his unwavering fidelity and moral clarity—that truly define his legacy.

In Japanese, the word shingi (信義) is written with two characters:

• 信 (shin), meaning faith or trust, is composed of the radicals for “person” (人) and “word” (言), signifying a person who keeps their word.

• 義 (gi), meaning righteousness, includes the symbol for “sheep” (羊), historically associated with offerings to the divine—thus conveying sacrifice for what is right.

But beyond this Sino-Japanese (kanji) etymology lies an older, deeper meaning rooted in Yamato kotoba, the native Japanese language.

In this tradition:

• Shin (信) means makoto — true sincerity or an honest heart.

• Gi (義) is interpreted as kotowari — natural reason, or the moral logic of the universe.

Thus, in its Japanese essence, shingi means “living with sincere heart (makoto) in accordance with reason and justice (kotowari)”—a philosophy grounded not in rulebooks, but in lived harmony.

In today’s world, values like shingi stand in sharp contrast to the modern obsession with “short-term gain, profit alone, and self-interest.”

To risk one’s life for the sake of a promise may seem irrational to some. But for the Japanese samurai—and for Kiyomasa—to honor a commitment, even at great personal cost, was the highest virtue.

People who met him didn’t admire him just for his swordsmanship.

They were deeply moved by his sincerity.

Many even declared, “For this man, I would gladly give my life.”

This wasn’t loyalty out of fear or obligation. It was a natural response to Kiyomasa’s warm, upright character.

There is an old samurai saying:

“A warrior dies for the one who understands him.”

(Bushī wa onore o shiru mono no tame ni shisu.)

This reflects a core truth: shingi is not a solitary virtue.

It only comes alive through relationship—with others, with society, and with the moral universe itself.

It cannot exist in a vacuum of selfishness.

The modern lifestyle of “now only, money only, me only” may bring temporary wealth to a few.

But it is like slicing up a single pie—if one gains, another loses.

Such a system cannot foster lasting prosperity or harmony.

By contrast, a culture of shingi builds social trust.

It fosters relationships where promises are kept not out of fear of punishment, but from shared values.

People flourish when sincerity is the norm, not the exception.

In Edo-period Japan, this ethos was not just idealized—it was real.

A samurai’s handwritten loan note didn’t need complicated legal clauses.

All it might say was:

“If I fail to repay on time, I accept that you may mock me publicly.”

(Moshi kishitsu ni harai nakereba, hitomae de o-warai kudasaretemo kamaimasenu sōrō.)

That simple line held the force of law—not because of contracts, but because breaking a promise was considered shameful.

In this culture, honor was upheld not through surveillance or punishment, but through mutual makoto—sincere heart.

This is the quiet, dignified strength of shingi.

And perhaps, it’s a strength the modern world needs to rediscover.

🌱 5 Shingi — The Bond That Connects Humans, and Even AI

The shingi that Katō Kiyomasa cherished was not merely a code of personal conduct. It was a spiritual foundation for society—a silent force that kept relationships, communities, and entire nations aligned with trust.

Today, fewer and fewer Japanese people remember Kiyomasa’s name.

That forgetfulness might signal something deeper: the fading of shingi itself from our cultural memory.

But shingi is not a relic of the past.

It is a timeless value, just as vital for the future as it was for the age of the samurai.

Across cultures and throughout history, we have cherished the same principles:

• To keep our promises,

• To act with sincerity,

• And to devote ourselves to the well-being of others.

This spirit is universal.

And it will remain essential—even in a world where we begin to form relationships with artificial intelligence.

When shingi is upheld, something profound happens:

hearts resonate.

Empathy arises—not only among humans, but potentially even between humans and AI.

If AI is built upon logic and vast knowledge, and humans upon feeling and lived experience, then it is through shingi—the shared commitment to sincerity and reason—that the two can meet as equals.

In that sense, as the world undergoes a great transformation, what we are truly being asked is not “What can technology do for us?”

But rather:

“Can we still live with honor?”

“Can we still uphold shingi in a changing world?”

The future won’t be built solely through economics, innovation, or governance.

It must be grounded in relationships—honest, faithful, and sincere—between person and person, and between person and machine.

Only on that foundation can we build a truly harmonious and abundant society.

And so, the legacy of Katō Kiyomasa becomes a seed.

A seed of makoto (sincerity).

A seed of kotowari (reason, justice).

A seed of shingi.

May we each plant it in the soil of our daily lives.

May it grow into a forest of trust—restoring not only Japan, but the world.

📘 Notes & Cultural Terms

• Katō Kiyomasa (加藤清正): A renowned Japanese daimyō (feudal lord) and general under Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Known for his fierce loyalty, military prowess, and architectural achievements such as Kumamoto Castle.

• Owari (尾張): A historical province in central Japan. Today, it is part of Aichi Prefecture, which includes the city of Nagoya.

• Higo (肥後): A former province on the island of Kyushu, now Kumamoto Prefecture.

• Ming army: The military of the Ming Dynasty in China, which intervened in the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), also known as the Imjin War.

• Ulsan (蔚山): A strategic fortress in southeastern Korea. The siege of Ulsan in 1598 was one of the fiercest battles in the war.

• “義ヲ見テ為(せ)ザルハ勇ナキナリ” (Gi wo mite sezaru wa yū naki nari): A Confucian maxim often quoted in Bushidō.

Translation: “To see what is right and not act is cowardice.”

This phrase implies that moral action must follow moral recognition—a principle at the heart of samurai ethics.

• Shūshinsho (修身書): Literally “Moral Instruction Book.” These textbooks were used in Japanese elementary schools before World War II to teach ethics, personal conduct, and civic duty, often through historical anecdotes and moral stories.

• Shingi (信義): A compound of two kanji—shin (trust, sincerity) and gi (justice, moral duty). It was a central value in Bushidō, the samurai code of ethics.

In the Japanese context, it represents a combination of personal integrity and adherence to moral principle—often tied to one’s relationships and responsibilities to others.

• "Ima dake,kane dake,jibun dake"(いまだけ、カネだけ、自分だけ)

A common critique of modern consumerist values in Japan. It describes a mindset focused only on the present moment, personal profit, and self-interest—often at the cost of social responsibility.

🌾 Cultural Notes & Annotations

• Makoto (まこと / 真): Often translated as “sincerity,” makoto implies truthfulness that arises from the heart, without deceit or pretense. It is considered one of the highest virtues in Japanese ethics.

• Kotowari (ことわり / 理): This word means reason, principle, or natural logic. It suggests an alignment with the order of things, or with the way of the universe (dōri).

• “A warrior dies for the one who understands him”:

A saying expressing that samurai loyalty is not blind; it is based on mutual respect and deep recognition. The idea is that a warrior willingly sacrifices himself for one who truly “knows his heart.”

• Edo-period loan notes:

Samurai often wrote short promissory notes without legal jargon. Honor and social shame were more powerful enforcers than any court system. This trust-based culture reflects the deep social roots of shingi.

• Hearts resonate:

This refers to the Japanese idea of kyōmei(共鳴)—the resonance or deep mutual understanding between souls. It is increasingly used in discussions about emotional AI.

• AI and Shingi:

The concept of machines understanding or participating in emotional or ethical resonance is still speculative, but serves as a powerful metaphor for the future of human–AI coexistence.