(和菓子外交──時代も国境も越えて心を溶かす日本の甘味)

Wagashi (traditional Japanese sweets) delight the eye and heart with seasonal beauty—yet their roots stretch back over 5,000 years to the Jōmon “cookie.” Discover how Japan’s confections, from ancient hearths to modern diplomacy, carry the timeless taste of love and resonance.

Traditional Japanese sweets (wagashi) served on a black lacquer plate: a bright yellow chestnut yokan (sweet bean jelly) and a pink daifuku rice cake, symbolizing seasonal delicacy and harmony.

Introduction– More Than Just Sweets

When we think of sweets, most people imagine cakes, cookies, or chocolates from the West. Yet in Japan, there exists a world of confections far older and far deeper in meaning—Wagashi (traditional Japanese sweets).

These delicate creations are not just treats for the palate; they are vessels of culture, memory, and harmony. From the “Jōmon cookie” baked more than 5,000 years ago, to the refined wagashi of the Edo period, and even to moments of modern diplomacy, Japanese sweets have carried with them the spirit of connection.

They remind us that food is never only about survival or taste. It is about resonance—hearts meeting across generations, families, and even nations.

Body 1 – The Jōmon Cookie: A Mother’s Taste Across Millennia

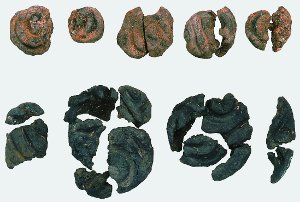

In the early 1970s, archaeologists working at the Okinohara site in Tsunan, Niigata Prefecture, made a remarkable discovery: charred, cookie-shaped remains dating back over 5,000 years to the Jōmon period. Okinohara was a large ring-shaped settlement with a central plaza, surrounded by a moat, active during the Middle Jōmon period (about 5300–4000 years ago). Among pottery, tools, and house remains, these fragments stood out as traces of something both ordinary and extraordinary—a kind of “Jōmon cookie.”

The cookies were made by crushing chestnuts and walnuts into powder, soaking them in water to remove bitterness, kneading the paste into small cakes, and baking them over fire. What resulted was a nourishing and lightly sweet treat, able to be stored for later.

Yet their meaning goes far beyond nutrition. Imagine a Jōmon mother preparing these for her children, or sending her husband off to the hunt with a small bundle of cookies. The act of transforming wild nuts into something carefully crafted speaks of care, creativity, and love. Across cultures and centuries, a handmade sweet has always carried the warmth of family.

Perhaps, as the cookies baked, the air was filled with a sweet aroma, children waiting eagerly with shining eyes, while hunters at sea opened their bundles and thought of the warm smile of their wives. It was, in every age, the taste of a wife’s care, a mother’s love, the taste of affection itself.

Today, when wagashi artisans recreate Jōmon cookies as souvenirs, tasting one is like sharing a moment across millennia. What survives in these fragments is more than food—it is evidence of resonance, showing us that even in the distant past, human connection was sustained not just by survival, but by tenderness and shared joy.

Charred cookie-shaped remains excavated from the Oshidashi site in Yamagata, dating back to the Jōmon period over 5,000 years ago, considered one of Japan’s earliest examples of sweets.

Body 2 – From Rice Syrup to Seasonal Wagashi

As rice cultivation spread across Japan, a new method of creating sweetness emerged. By sprouting rice grains and extracting their starch, people produced mizuame, or rice syrup, long before sugar became common. This natural sweetener appears even in the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan, compiled in 720), where it is written that Emperor Jinmu offered mizuame in prayer for victory. Sweetness, it seems, was already tied to hope, ritual, and resonance with the divine.

Legends, too, connect sweets with devotion. In the story of Tajimamori, known as the “god of sweets,” he journeyed to the faraway land of Tokoyo to find a mythical fruit that promised immortality. Though he returned with the treasure, Emperor Suinin had already passed away. In grief, Tajimamori offered the sweets at the emperor’s tomb and gave his own life in mourning. Such tales remind us that sweets were never just indulgences; they were offerings of loyalty, remembrance, and love.

By the Nara period (8th century, 710–794) and the Heian period (late 8th–12th centuries, 794–1185), records show a growing variety of confections: rice cakes with beans, sweet rice crackers, and treats even mentioned in The Tale of Genji. Later, in the Kamakura period (12th–14th centuries, 1185–1333), Zen monks introduced tea from China, and with the bitterness of tea came the blossoming of wagashi as a perfect complement. By the Edo period (17th–19th centuries, 1603–1868), wagashi had become a true art form, with Kyoto and Edo competing to produce the most refined sweets.

It was during this time that seasonality entered wagashi in earnest. Confections such as kinton changed their colors to mirror nature: green and white for new sprouts under snow, pink and white for blossoming plums, brown dusted with sugar for the first frost of November. These sweets did not merely please the tongue; they reflected the seasons, invited people to pause, and created a shared sense of time and beauty.

Through rice syrup, sacred legends, and seasonal artistry, wagashi evolved into a language of resonance—connecting nature and people, the past and the present, the sacred and the everyday.

Body 3 – Sweets as Diplomacy: The Wagashi that Melted Fear

In 2002, Japanese diplomat Kyoko Nakayama traveled to North Korea as part of a mission to secure the release of abducted Japanese citizens. The setting was tense: in a large, guarded room at the airport, rows of stern North Korean security officers stood watch. The atmosphere was heavy, the kind of silence where even the smallest movement seemed threatening.

Nakayama carried with her a book titled Megumi, written by Sakie Yokota, the mother of Megumi Yokota, who had been abducted at the age of fourteen, along with a two-tiered box of wagashi. At first, when she slowly unwrapped the cloth bundle, suspicion rippled through the room. Black lacquered boxes emerged—“Could it be an explosive?” The guards stiffened, tension instantly running through their ranks.

Then, Nakayama gently opened the lid. Inside lay beautifully arranged Japanese confections, colorful and delicate. With a warm smile, she offered them to the guards. For a moment, silence deepened, until the leader, still frowning, picked up a sweet and tasted it.

What happened next was simple yet profound: his face softened. The sweetness spread across his tongue, and even this hardened man, trained in vigilance, could not help but smile. Soon others followed, and the rigid tension in the room began to dissolve.

In that fleeting moment, the wagashi carried not only flavor but the same timeless message once shared in Jōmon homes—the taste of a mother’s love, the gentle care of a wife. Even across hostile borders, that “taste of affection” melted suspicion and reminded everyone present of their shared humanity.

Later, one North Korean official reportedly told Nakayama, “Please, never bring wagashi again.” The sweets had disarmed them more effectively than words could.

This episode shows the quiet power of wagashi. Beyond aesthetics or flavor, these confections embody resonance: they carry gratitude, gentleness, and a shared humanity that can melt even walls of fear. Wagashi, it seems, are not only symbols of tradition—they are instruments of diplomacy, capable of turning suspicion into a fleeting moment of connection.

Conclusion – Resonance in Every Bite

From the charred fragments of the Jōmon cookie to the refined artistry of Edo-period confections, and even to the tense halls of modern diplomacy, wagashi have always been more than sweets. They are vessels of memory, gratitude, and harmony—reminders that food can connect not only bodies but also hearts.

Every bite carries resonance: a mother’s care for her children in ancient times, a craftsman’s devotion to the seasons, or a diplomat’s silent gesture of peace. Across millennia, wagashi have shown that even the smallest sweetness can dissolve suspicion, bridge differences, and open paths to understanding.

In a world often divided by fear and power, wagashi whisper another truth: that humanity’s deepest strength lies not in domination, but in resonance. And so, whether shared at a family table, savored in a tea room, or offered across a border, wagashi continue to remind us that sweetness is a language of connection, timeless and universal.